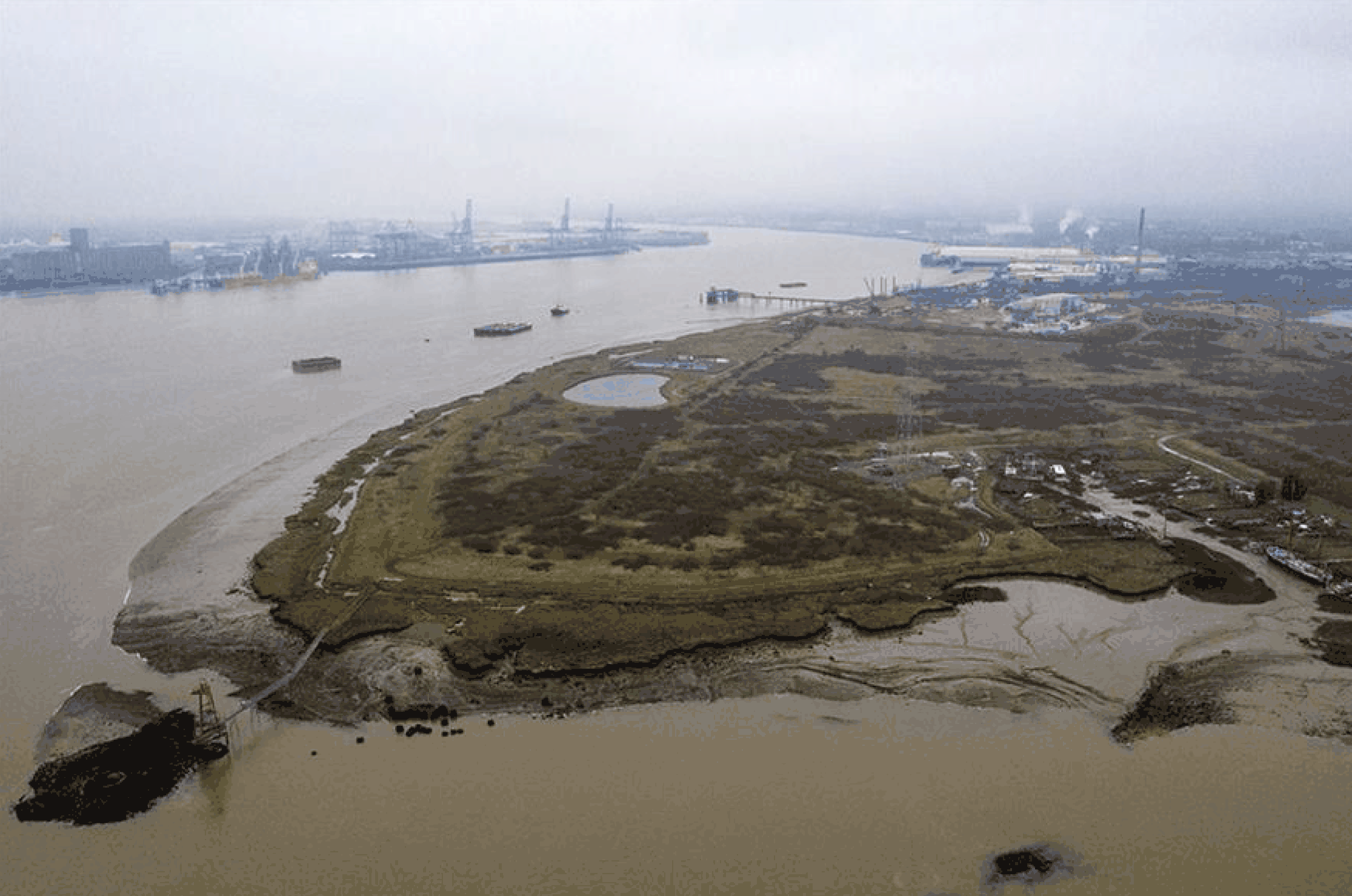

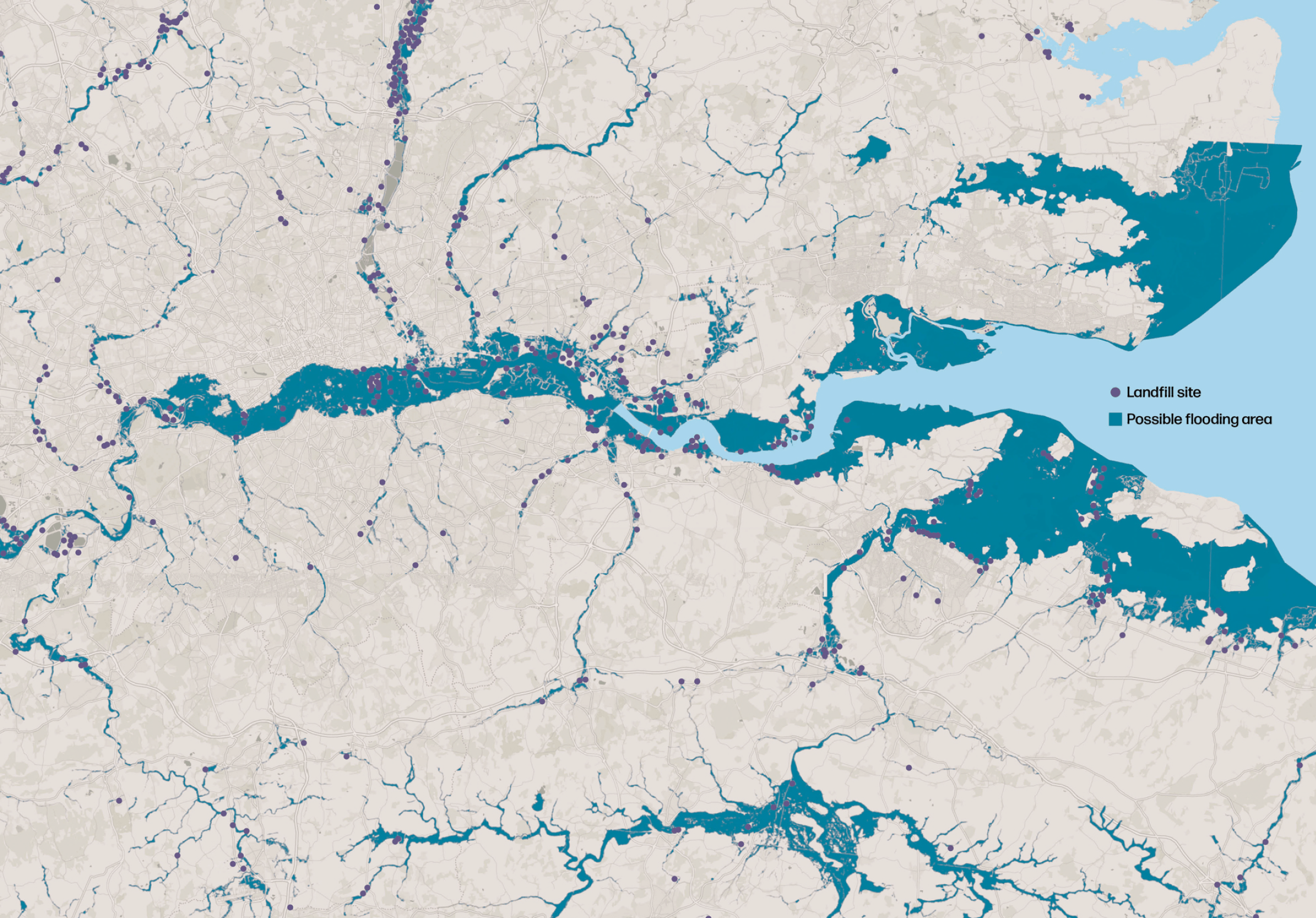

Some 4,781 historic landfill sites across England lie within flood zone 3. Photograph: Getty Images/Dan Kitwood

Hundreds of historic landfills are located in areas susceptible to flooding, an analysis by ENDS has found.The finding adds to growing concerns that old tips could become major sources of pollution as a result ofclimate change if no action is taken to protect them

It’s a shocking statistic. Some 4,781 historic landfill sites across England lie within flood zone 3 – areas considered to have a 1% orgreater probability of flooding from rivers or 0.5% or greater probability of flooding from the sea, according to an analysis by ENDS.In addition, more than 1,500 historic sites across England are in areas that have flooded at least once in the past 50 years, analysisreveals.

Using Environment Agency (EA) data, ENDS has identified 1,555 historic landfills, many of which are unlined, making themvulnerable to heavy rain and flooding. The figures highlight a possible need to “re-engineer” such landfills in the face of climatechange. Some sites are known to be already leaching harmful chemicals into the environment.

The possibility of more intense rainstorms as a result of climate change has raised concerns among experts that these landfills willbecome major sources of pollution if no action is taken to protect them.

“We have a lot of old landfills that are on the coast and a number of them are old chemical waste landfills,” says Dr CeciliaMacLeod,an expert in contaminated land from the University of Greenwich. “You have to have a system where you’ve got continual sea defences in order to protect the seaside. If those chemicals start to leach from the landfill into the estuary then it’s going tocause a disaster.”

More than 1,200 historic landfill sites are at risk of coastal erosion and storm surges, according to Professor Kate Spencer and hercolleagues at Queen Mary University, who have studied the potential of these sites to cause pollution.

In one site, built as a flood embankment in the 1980s, the team found heavy metals and organic contaminants leaching into theground and lying open on the beach. Named Hadleigh Marsh, the site contains a mixture of commercial and household waste that istypical of many other landfills of the era.

“We found that at every site we visited in the Thames estuary, there is evidence it has been leaching for decades,” says Spencer.“We know some sites are eroding and releasing toxic material onto beaches and you can go there and visit it and see it. The risk willincrease because the longer you go on, the more likelihood there is of one of these big impact events like a heavy rainfall or a highstorm surge.”

The winter of 2015, which saw 11 named storms over the season, demonstrates what can happen. Extreme weather eroded thebank of the river Ericht near Blairgowrie, Scotland, and the waste from a former landfill collapsed into the river.

A report by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency said: “Although no leachate was visible entering the river Ericht, largeamounts of plastics and metals were exposed and general waste was being washed downstream.” The remaining waste had to beremoved and capped – 3,000 tonnes of it – and the riverbank rebuilt at a cost of £80,000.

Other landfills that are safe from erosion can still threaten the environment, as rainwater percolating through the waste createspathways for contaminants to escape. “It’s a transport mechanism,” says MacLeod.

“If we look at historic landfills in the UK that were built before legislation [came in], most of them are in old quarries and they’re notlined with anything. So, if you have water that’s infiltrating into these old quarries, then there is the potential for that water to leachinto the groundwater system.”

Forever, everywhere

This is already happening with a group of chemicals that are water-soluble, highly mobile, toxic, persistent, bioaccumulative and canonly be destroyed through incineration: per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

Nicknamed ‘forever chemicals’ because of their ability to outlive generations of human beings, PFAS substances are highly prized inmanufacturing because of their resistance to heat, water and oil. They have been used for more than 50 years in a wide range ofconsumer goods such as non-stick pans, waterproof clothing, carpets and food packaging – products typically ending up in landfill.

The amount of PFAS produced globally is a mystery and only a tiny fraction of the estimated 4,700 chemicals within the group arebanned under the Stockholm Convention.

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) are the most notorious, having been linked withhypercholesterolemia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, thyroid disease, testicular and kidney cancer and ulcerative colitis.

The health effects of the thousands of other chemicals within the group are unknown, but they should be treated with the samecaution as PFOA and PFOS, says Dr Kerry Dinsmore of the environmental charity Fidra, because conclusive research would takedecades.

“They’re very hard to contain,” she says. “They can come out in the leachate but they can also be volatised [converted into a gas orvapour]. Even if we don’t know if they’re toxic or not, the fact that they’re very persistent and mobile, that in itself is usually reasonenough to control them.”

She adds: “In Denmark, they’ve put in restrictions so you can no longer intentionally add them to paper food packaging, but theycan’t say zero PFAS because there’s no such thing as zero PFAS anymore… The very fact that you need water to produce papersays that there will be a level of PFAS in that paper that you can’t get rid of. We’re at that point of environmental contamination thatwe cannot make products without PFAS in them.”

An EA draft report from 2020 identified landfills as one of the largest sources of PFAS in the UK and it is now so widespread thatwhen the Chemicals Investigation Programme tested river water at more than 600 sites across Britain, it found PFOA and PFOS inall samples.

Dinsmore advocates the need to prove something is safe before putting it on the market instead of having to prove it is harmful totake it off, especially PFAS chemicals used in single use packaging.

“You go get a sausage roll, you walk out of the shop and put your paper bag straight in the bin, because you’re eating on the go. So,you’ve had that piece of paper for 30 seconds and yet there are chemicals in it that will last for thousands of years. It’s insane.”

Leaky defences

The EA says it is not responsible for regulating historic landfills and it is up to local councils to identify and report contaminated land.But councils may not be taking PFAS into account when investigating sites. That, it goes without saying, is a major hole in thenation’s defences.

“Because the analysis is so expensive, it’s not routinely monitored,” says MacLeod. “As PFAS has become more of a concern, moreand more people are buying the analytical instruments and that brings the price down.”

While much of the research on old landfills has examined the slow, long-term release of contaminants into the environment, thecase of seven-year-old Zane Gbangbola, who was killed after floodwater entered his Surrey home in 2014, shows the potential forold sites to pose an immediate danger to human life.

Zane’s parents, Kye and Nicole Gbangbola, are calling for an independent inquiry and say they have key evidence linking their son’sdeath to a highly toxic gas – hydrogen cyanide – that they argue could only have come from a historic landfill site next to their home.This evidence was not included in the coroner’s inquest report, which concluded that carbon monoxide from a petrol pump killedZane. The coroner said the family used the pump indoors while clearing floodwater from their basement.

But when Surrey Fire and Rescue’s HAZMAT team arrived on the night Zane died, it took multiple readings of hydrogen cyanide, upto 25,000 parts per million, according to his parents. A Public Health England toxicological overview for hydrogen cyanide states that270ppm is enough to cause immediate death through inhalation.

“We were out of the house for over a year,” says Kye Gbangbola, who was left paralysed by the same gas that killed his son. “All ofour medical records had hydrogen cyanide, even entries from Porton Down saying: ‘you can’t go back to the house, hydrogencyanide found in pockets in the house.’ For carbon monoxide, you don’t call in Porton Down.”

Porton Down is a highly secretive government facility tasked with researching chemical and biological weapons.

In early 2020, a Ministry of Defence engineer told the BBC he believed chemical waste from a nearby tank-testing facility wasdumped in the landfill next to the Gbangbola’s home and claimed it could produce cyanide.

But because of the government’s refusal to open an independent inquiry, the link between Zane’s death and the landfill remainsunder-explored in court and therefore unproven.

“There are many historic landfill sites that aren’t protected throughout the UK and with widespread flooding it’s a new territory,” saysNicole Gbangbola. “We really need to look at these sites and make sure that homes built around them are protected, so whathappened to Zane never happens again.”